Ebola spread to Uganda could threaten international health

After smouldering in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for almost a year, killing near 1,000 people, the deadly Ebola virus crossed the border to Uganda in June 2019. This virus causes sudden high fever and sore throat, with severe weakness and muscle pain. It quickly progresses to vomiting and diarrhea, with signs of internal and external bleeding. It is transmitted through contact with body fluid from an infected person. The fatality rate is high.

Surveillance for ebola virus disease at the border between DR Congo and Uganda | Photo: Matt Taylor

The DRC outbreak is the second largest ever recorded and the worst ever in this country.

The first Ugandan case reported on June 11 was a 5-year old boy whose grandfather in DRC had just died of Ebola. His Ugandan family, who had crossed the border to care for their father, returned home just a few days before the boy fell sick, followed by two others. Two of them died shortly afterwards. The remaining family members were given passage back over the border, while several other contacts with high fever, also from the DRC, were put in isolation. However, many of them absconded from the treatment center.

Other contacts have been identified, and advised to remain at home to be vaccinated against the disease. Uganda is in a state of Ebola alert, which was initiated since the DRC outbreak began. There have been no mass gatherings, and information about the disease is being broadcast continuously. Almost 4,000 health workers have received vaccination, and screening camps are operating all along the border with DRC, and other major portals. Places at high risk because of high people mobility and proximity to the border are being monitored constantly for spot diagnosis and management of any cases.

Uganda will begin ring immunization on June 14 to contain the spread of the virus by immunizing direct contacts and their contacts. A rapid response team is already in place to identify those at high risk. 400 doses of Ebola vaccine have been sent in by the DRC with another 4,000 doses from the WHO. This new vaccine prevents infection in almost 98% of cases.

The WHO Emergency Committee will also sit for the third time to decide whether to declare the DRC outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern,” or PHEIC, which will attract international help in dealing with it.

The DRC epidemic began in August 2018, with almost 2,100 cases so far and counting. Civil conflicts have made it difficult to control the illness, with approximately 200 medical facilities being attacked on several occasions this year. As a result, health workers have been forced to suspend operations in some centers where the disease is raging. Despite this, WHO has not declared it a PHEIC so far.

Other countries are taking their own precautions. Rwanda has already decided to police its borders, and its people are being exhorted to stay away from virus-rife areas. Vaccination is being promoted among health workers who come in contact with possible contacts.

Ebola is primarily an animal disease, with the virus taking shelter in bats and other mammals. It may spill over into the human population when someone eats an infected bat, for instance. However, such events usually end spontaneously with a chain of not more than 5 people.

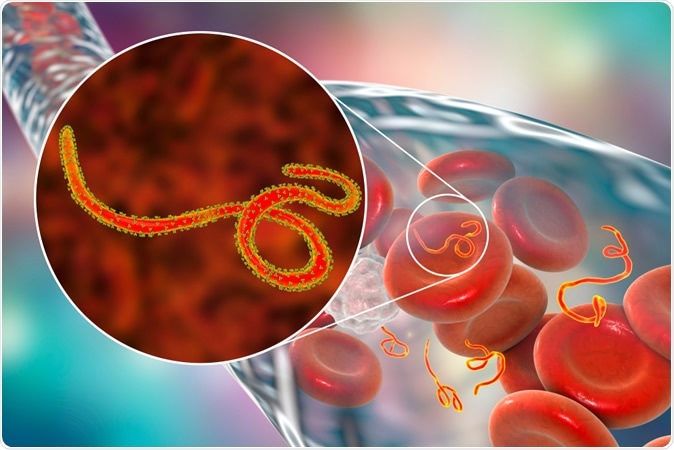

Ebola viruses in blood of a patient with Ebola hemorrhagic fever, 3D illustration - Illustration Credit: Designua / Shutterstock

Researcher Emma Glennon modeled the size of likely distributions using available datasets on Ebola outbreaks from three countries in West Africa. She found that compared to the reported size of the outbreak in these places, only about 17% to 48% were actually reported. In other words, about half of all outbreaks are never reported. When it comes to single cases of infection, dying out without spreading any further, the chances of detection are below 10%. Glennon remarks, “Early detection of outbreaks is critical to timely response, but estimating detection rates is difficult because unreported spillover events and outbreaks do not generate data.”

This research points to the importance of identifying outbreaks as early as possible before many people are infected. However, it also explains why many people in these countries show the presence of antibodies to Ebola. Clinically recognized outbreaks include only symptomatic cases, and if over 80% of single cases or small outbreaks are missed, this could be the reason for the presence of these antibodies, says Ian Mackay, at the University of Queensland in Australia.

Source:

- Confirmation of case of ebola virus disease in Uganda, https://afro.who.int/news/confirmation-case-ebola-virus-disease-uganda

No comments:

Post a Comment