Cancer chemical from common gut microbe

Many common gut bacteria carry cancer-causing mutations, says a new study published in the journal Nature on the 27th February 2020.

The background

There are trillions of bacteria living in and on the human body. The gut bacteria within human individuals play a unique role in both health and disease. They prime immunity during the formative 2-week period just after birth, they prevent the invasion and overgrowth of pathogenic bacterial species and maintain the integrity of the intestinal epithelium, among other things.

A potential pathogen that occurs commonly in the human gut is the bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli).

Escherichia coli bacterium, E.coli, gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria, part of intestinal normal flora and causative agent of diarrhea and inflammation, 3D illustration: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Mutations and tumor development

Cancer cells develop because of specific mutations in the DNA, which cause unbridled proliferation and loss of mature characteristics, in many cases, resulting eventually in tumor growth. Mutations are often caused by exposure to ultraviolet light or smoking. Repeated exposures increase the chances of harmful mutations accumulating within a cell, causing cancerous transformation.

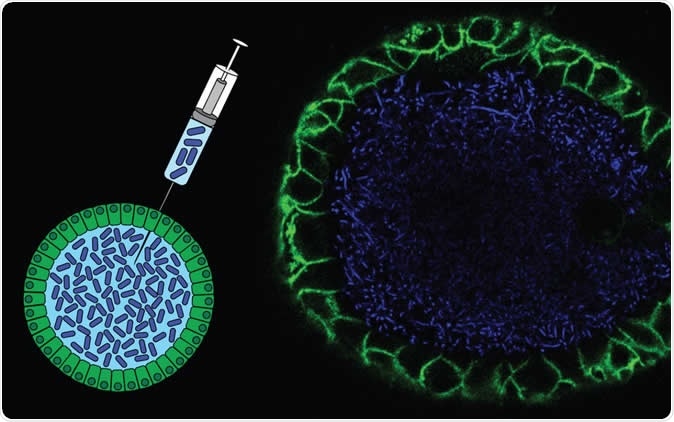

Schematic representation of the injection of bacteria into the lumen of an organoid, and a fluorescent microscopy image of such an organoid. Human intestinal organoid (green) filled with labeled bacteria (blue). Image Credit: Cayetano Pleguezuelos-Manzano, Jens Puschhof, Axel Rosendahl Huber, ©Hubrecht Institute

It is known that every type of DNA damage causes a visible pattern of DNA damage called a mutational signature or footprint. Many such footprints are already known, which record the effect of agents such as ultraviolet exposure or smoking. Thus, the exposure history can often be known by looking at the mutational footprint. However, the mutagenic effects of gut bacteria were unknown until recently.

As researcher Ruben van Boxtel explains, “These signatures can have great value in determining causes of cancer and may even direct treatment strategies. We can identify such mutational footprints in several forms of cancer, also in pediatric cancer. This time we wondered if the genotoxic bacteria also leave their unique distinguishing mark in the DNA.”

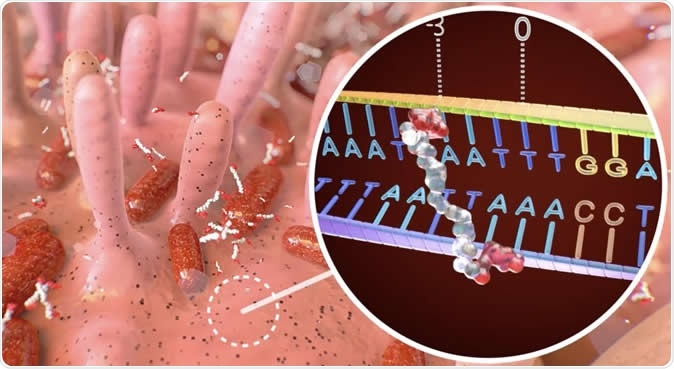

Illustration of colibactin binding to specific DNA sequence. Image Credit: DEMCON | nymus3D, ©Hubrecht Institute

The study

In the current study, the investigators looked at intestinal organoids, which are tiny masses of intestinal tissue grown as a mini-organ in the laboratory, to test whether a specific strain of E. coli induces DNA mutations. This strain is found in a fifth of all adults.

The researchers cultured gut organoids which were then exposed for five months to this strain of E. coli, which produces a genotoxin, a chemical that harms the human DNA. The chemical involved is called colibactin. The gene-modifying effects of this toxin mean that it could harm humans by causing mutations.

After 5 months of exposure, the organoid cells were subjected to DNA extraction, and the kind, as well as the number of mutations due to the bacterial presence, was analyzed.

The results

The researchers found that there was indeed a unique pattern to the mutations that occurred within the organoid cells. In other words, the tested strain of E. coli did cause a distinctive mutation pattern to occur within human cells.

The signature consisted of two mutations that occurred together, one being the change of an adenine base (A) to any of the other four DNA bases, and the other the loss of a single A in long polyA stretches. There was also another additional A on the other strand of the DNA helix, located at a distance of 3-4 bases away from the site of mutation.

Delving deeper

At the final stage, the team began to explore the way colibactin caused DNA damage. They found out its molecular structure and how this acted upon the DNA. The chief finding was that colibactin could bind two A’s simultaneously, causing a crosslink to form between them. This could, in their opinion, explain why the colibactin caused its unique mutational pattern.

The next step was to trace this signature in other cells, namely, the cells of patients with cancer. Furthermore, the researchers did not skimp on this. They examined thousands of mutations in over 5,000 cancers, of many different types.

One exciting finding stood out: more than 5% of bowel cancers showed this footprint, but it was present in less than one in hundred of other cancer DNAs. Among these, the tissue was known to be exposed to the same bacterium – such as cancer of the mouth or the urinary bladder.

Ominously, this tell-tale pattern was also found within the DNA of patients with colon cancer, which may well indicate a link between the bacteria and the disease. Jens Puschhof says, “It is known that E. coli can infect these organs, and we are keen to explore if its genotoxicity may act in other organs beyond the colon.”

Implications

This study marks the first time a direct connection has been found between the human microbiome and the mutations that cause cancers to develop.

The frightening thing is that, in the words of Hans Clever of the Hubrecht Institute, which ran the study, “There are probiotics currently on the market that contain genotoxic strains of E. coli. Some of these probiotics are also used in clinical trials as we speak. These E. coli strains should be critically re-evaluated in the lab.”

He explains that despite the short-term relief for certain painful conditions such as fibromyalgia or irritable bowel syndrome, when used for a short period, they could cause cancer after decades.

The finding of this mutation signature could help screen patients for their chances of developing a tumor, based on the presence of this genotoxic strain. It is estimated that it occurs in up to a fifth of healthy individuals. It is even possible that using the right antibiotics, these bacteria could be eradicated, and the chances of tumor development markedly reduced. Or at least, it could help detect these tumors very early in their course.

Journal reference:

Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C., Puschhof, J., Huber, A.R. et al. Mutational signature in colorectal cancer caused by genotoxic pks+ E. coli. Nature (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2080-8

No comments:

Post a Comment